A summary of research

This document summarises the findings of SANE’s research, and what it means for healthcare professionals – doctors, nurses, psychologists, counsellors, social workers, and other clinicians – supporting people living with personality disorder, their carers, and families.

Introduction

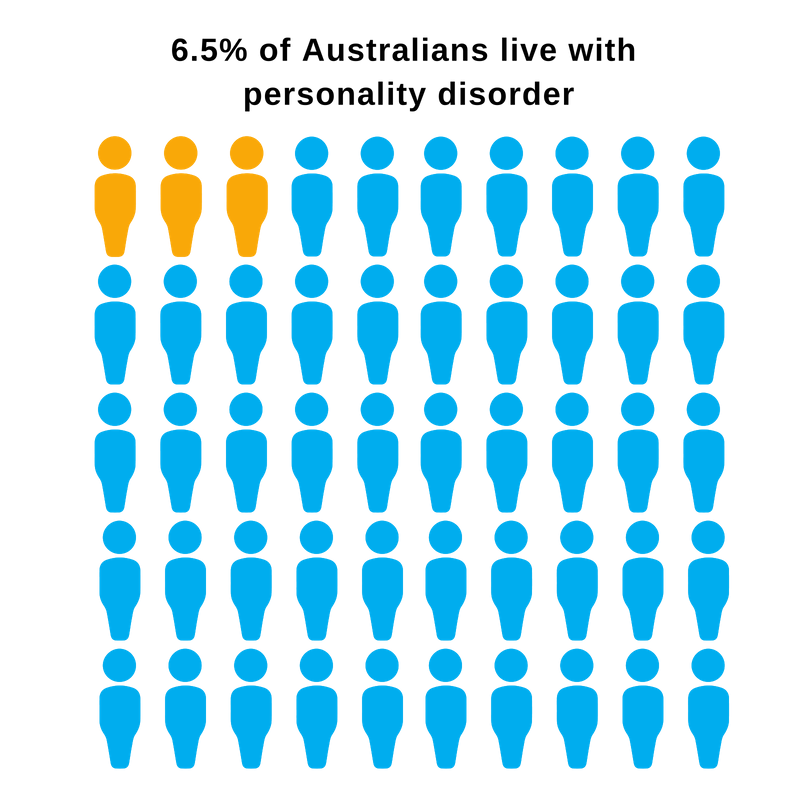

Personality disorder involves pervasive and persistent patterns of thoughts, emotions and behaviour that can be distressing, and make daily life difficult. Around 6.5% of Australians are believed to be living with personality disorder.

Living with personality disorder can be challenging. Providing care and support for someone with personality disorder can be rewarding and life-saving. But it can also be stressful. It can be difficult for people living with personality disorder, and carers, families and other support persons, to know where to find information and how to access support. Healthcare professionals also face challenges supporting people living with personality disorder. The right support is critical for recovery and improving quality of life.

In 2018, the National Mental Health Commission (NMHC) funded SANE’s research into how best to respond to the needs of Australians living with personality disorder. That project, which is now completed, involved research with people with lived experience of personality disorder. This current, complementary study was developed to understand the perspectives of healthcare professionals.

What are the key messages of the research?

- Many healthcare professionals want to provide comprehensive, tailored, and long-term support to those who need it. Unfortunately, Australia’s mental health system does not currently meet the needs of people living with personality disorder. Changes are required to enable healthcare professionals to provide more intensive, flexible and long-term support, tailored to individual needs.

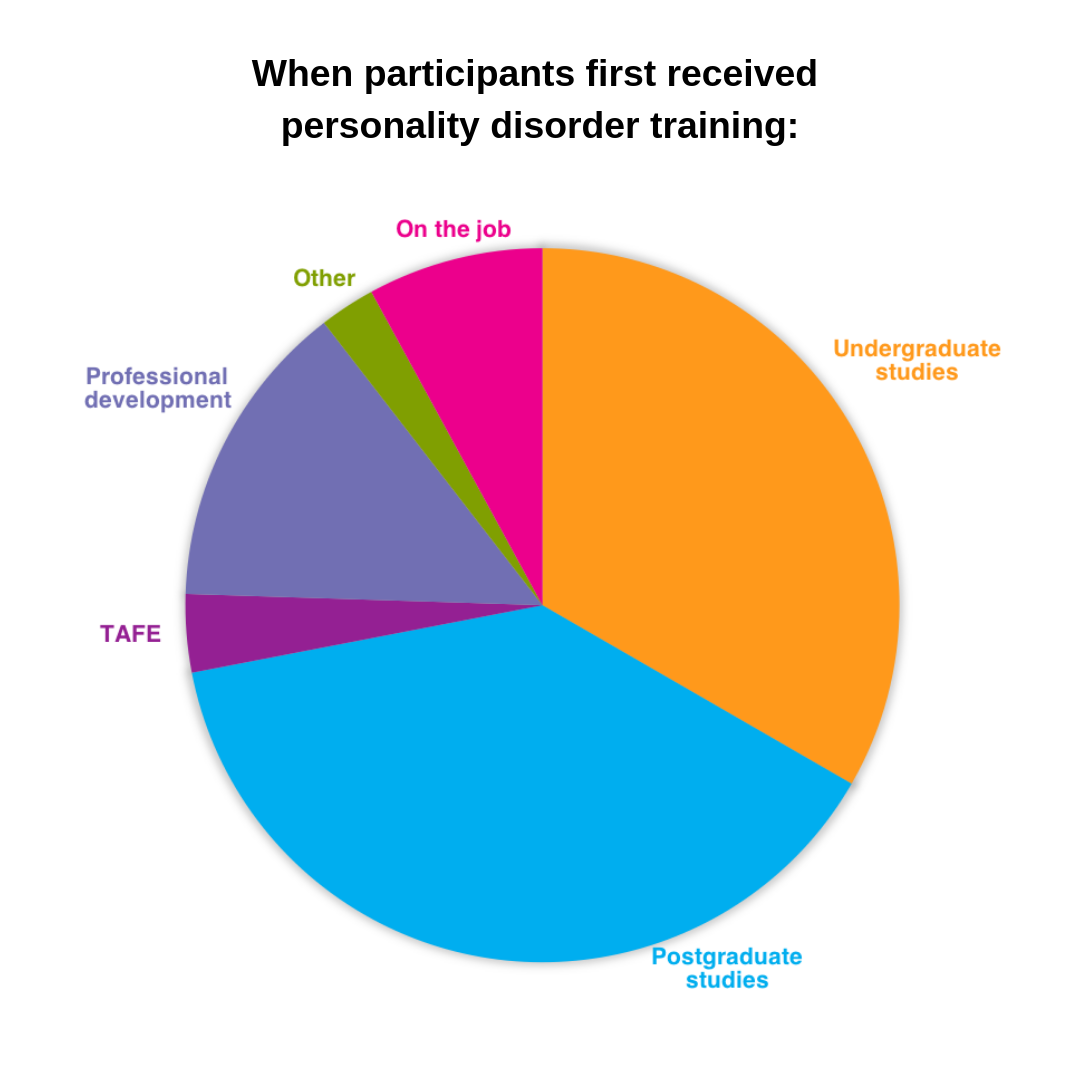

- Comprehensive personality disorder training tends to be self-driven, rather than being part of core training. More early-career education, as well as accessible and affordable training opportunities, are needed to 'upskill' healthcare professionals.

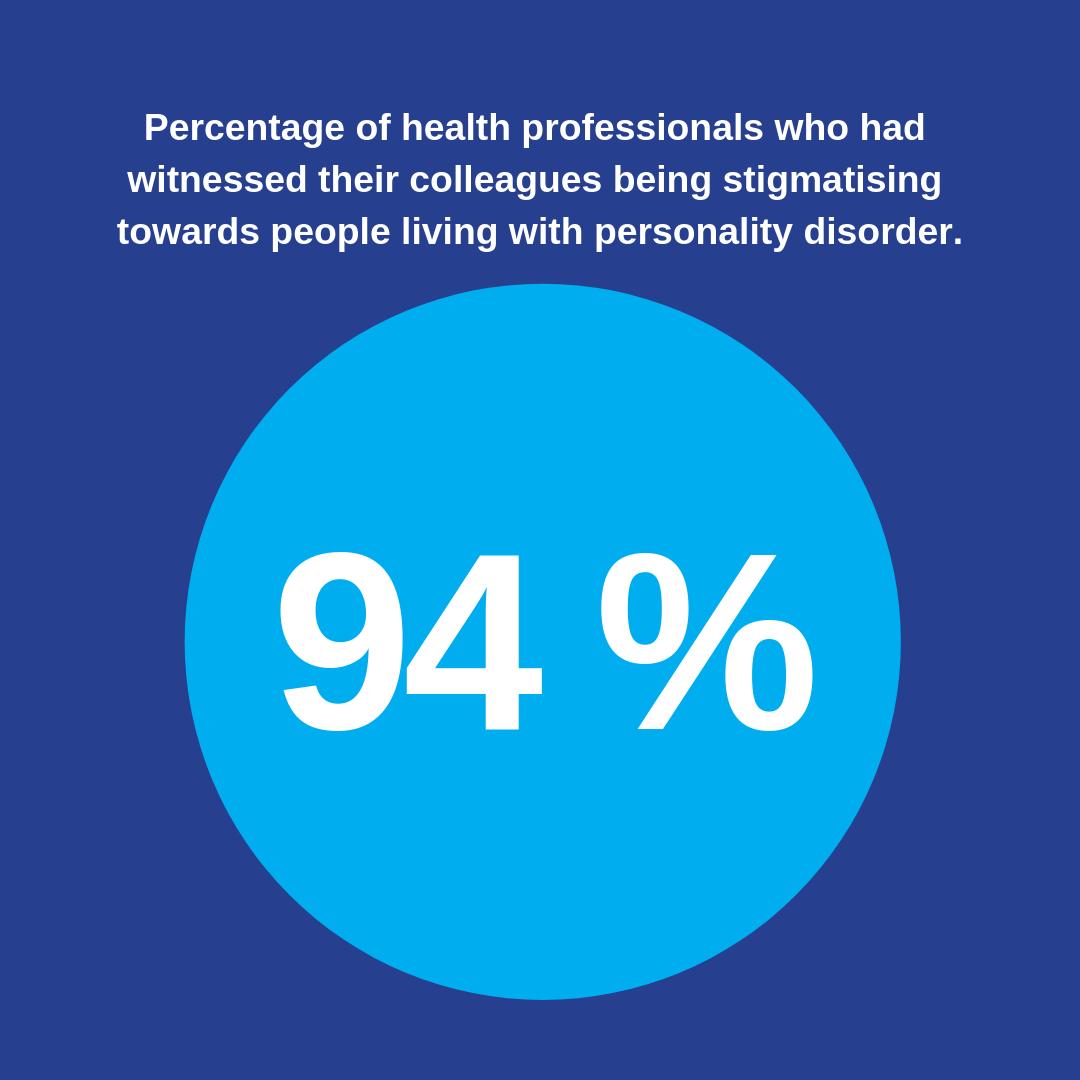

- Many healthcare professionals report a significant amount of stigma relating to personality disorder in their workplaces. They attribute this stigma to a lack of training in personality disorder, an over-focus on negative experiences, and burnout.

The research

Participants were asked questions about their experiences working with people living with personality disorder. These questions explored their attitudes, confidence, training history, and the challenges they encountered as a result of the way Australia’s mental health system is set up.

In total, 146 healthcare professionals participated in an online survey. Nine participants also completed in-depth interviews. Most participants were psychologists, mental health nurses, or social workers. Through these interviews, four themes were developed. Please note that all names have been changed.

The thriving clinician

The participants’ answers indicated that a certain type of person is drawn to working with people living with personality disorder. Healthcare professionals who thrive in this area tended to be empathetic and understanding. These ‘thriving clinicians’ sometimes had their own personal experience of living with mental illness or trauma.

When you work with clients who have really difficult life experience and really difficult experiences with services, it's really rewarding.

Rochelle*, 33, occupational therapist, provisional psychologist and rehabilitation counsellor

Word cloud of qualities participants identified as being integral.

Word cloud of qualities participants identified as being integral.

Expertise

A number of participants were uneasy about calling themselves personality disorder ‘experts’. Their responses suggest that professionals can experience self-doubt when working with people with personality disorder. However, participants also reported improvements in their therapeutic skills as a result of this work. They became more patient and developed a better understanding of the impacts of trauma throughout a person’s life.

Training was considered critical for supporting clinicians to increase their knowledge, confidence and competence, and challenging the myths and stigma around personality disorder.

Most participants said their own university training in personality disorder was minimal. Many said this early education was insufficient in scope and the bulk of their training took place on the job later.

Many also reported accessing additional specialist training (often self-directed and self-funded). Most who attended specialist training said it was high quality and valuable.

We never feel that we know enough, so we always have to go and get more training and keep ahead of the ball.

Marcus*, 51, clinical psychologist

Cultural shift

The participants said there has been a cultural shift in personality disorder awareness and advocacy, both within Australia and internationally. Increased awareness of trauma-informed practice has resulted in a shift in how healthcare professionals approach personality disorder. This study showed a direct correlation between a healthcare professional’s level of stigma towards personality disorder and the extent of shared decision-making with a consumer. Basically, the less stigmatising health professionals were, the more open they were to engaging consumers in the decision-making processes surrounding their treatment.

Despite this shift, most participants acknowledged significant stigma still exists. The data suggests healthcare professionals may be unintentionally contributing to this stigma. Some respondents noted that negative patient experiences are the most memorable, so these are the stories that tend to be shared between colleagues or friends. If negative stories are the ones that dominate, stereotypes will continue to dominate.

Sometimes when a patient is going really well it is not something that you think about. And then when they perhaps aren’t going that well, that becomes big ... [patients] that cause you the biggest headaches are probably the ones you remember the most.

Susanna*, 32, general practitioner

A patchwork approach

Because of gaps in services, health professionals often had to ‘work the system’ and to fulfil multiple roles – sometimes outside of their clinical skillset – in order to deliver the support the person required.

Participants reported having to ‘make do’ with whatever supports and services that were available in their region – a ‘patchwork approach’. Most stated that Medicare, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), and public hospitals were not meeting the needs of those living with borderline personality disorder.

Where we are [in remote QLD], we have nothing. No homeless shelter. No GPs that bulk bill anymore. So our clients just don’t go to the doctor and then they just go to the emergency department for everything. So that’s a real frustration, I think the government brought that in. So the clients are not going to the GP, and they are not getting their scripts because they cannot afford the $30 that they have to pay. So that is a challenge.

Barbara*, 61, mental health nurse

What does this all mean?

The information provided by participants suggests that in order to support people living with personality disorder, healthcare professionals need:

- more training, earlier in their careers, to improve knowledge and reduce behaviours that could be perceived as stigmatising

- changes in the way Australia plans, designs, and funds its mental health system so they can direct their patients to the support they need, when they need it.

These types of changes are obviously dependent on the support of public services and education providers. In the meantime, health professionals looking for more information about personality disorders can refer to resources such as:

- The Project Air Treatment Guidelines for Personality Disorders

- The NHMRC Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder

- The Australian BPD Foundation

- The Australian BPD Foundation and the Mental Health Professionals’ Network’s webinar library.

*All names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Further information

Contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. for more information about this project.